Feb 15, 2023

Debt Knowledge Series

Corporate Bonds Are Not For Beginners

An experiment in buying corporate bonds through the biggest retail brokerage firms.

On January 3rd, the first business day of the new year, I opened my laptop a few minutes before a remote team meeting scheduled for 8:30 AM. With some brief time to kill before others joined, I was happily able to complete the first item on my personal to-do list with a few clicks and thirty seconds of time. That’s all the effort it took to maximize an annual purchase of I bonds on TreasuryDirect, the direct-to-investor website for government bonds run by the US Treasury Department.

My decision to max out the investment limit imposed by Treasury was far from maverick.

I bonds – which feature inflation-protected rates and investment gains exempt from state taxes – have surged in popularity in recent years. On one single day last October, retail investors bought $979 million worth of I bonds, or nearly as much as Treasury had sold over the course of an entire recent three-year period (2018-2020). Investors that held from the start of 2022 were handsomely rewarded. In the worst year ever for most bond classes in the US – during which intermediate Treasuries and corporate bonds fell by 12.5% and 15.7%, respectively - I bonds still produced an enviable 9.62% gain.

However, TreasuryDirect boasts several features more permanent than the transient high performance of one particular bond series. In the argot of economists and other social scientists, investors face low monetary and non-monetary costs of participation. As examples of the former, the Fed charges no commissions and allows minimum buys as low as $25. And for non-monetary costs, a recent website revamp now provides users with a transparent and painless purchase process.

With current interest rates still at relatively high levels, after hitting the annual I bond limit, I decided over lunch that same day to look further afield for other sources of yield. And so, for the first time in my personal investing career, I considered buying individual corporate bonds.

Which one(s) to choose?

Unlike monotypic I bonds, over 30,000 corporate bonds trade in the US. As a first cut, I decided to stick to debt from the most durable, high-quality corporations. Lower-rated bonds seem risky when buying less than a handful of notes. Then, within the universe of investment grade names I narrowed the options further by eliminating companies that might be subject to disruption from the mainstreaming of AI-related technologies. I reasoned that the ratings agencies probably hadn’t fully appreciated AI risks when issuing grades in recent years. To get started – and admittedly without much in the way of systematic research - I looked for bonds from Proctor & Gamble and Amazon. Both companies produce or distribute physical goods. And since we’re still at least several years away from being able to fabricate tangible products from our couches by linking home voice assistants to 3-D printers, the bonds from those companies seemed to represent relatively safe investments.

The process for buying corporate bonds, however, proved more difficult than I anticipated. The user experience at TreasuryDirect easily outclassed the three online retail brokers I accessed that day in an effort to purchase corporate bonds. TreasuryDirect eschews bond market jargon while helpfully answering questions on a handsomely designed homepage that links to a clear discussion of interest rate formulation and a side-by-side comparison of different bond series.

The retail brokers, on the other hand, embrace jargon (e.g., “CUSIP”; “Ask Yield to Worst”). Links from terms to glossaries call up separate pages that direct to the first alphabetical listing in the glossary index rather than any precise term. No search functions are embedded within the glossaries so one needs to be prepared to scroll. After finally locating a term, definitions tend to have a whack-a-mole quality, employing further jargon that requires a separate lookup. Take, for example, the definition for yield on one broker site:

the percentage of return an investor receives based on the amount invested or on the current market value of holdings; it is expressed as an annual percentage rate; yield stated is the yield to worst — the yield if the worst possible bond repayment takes place, reflecting the lower of the yield to maturity or the yield to call based on the previous close

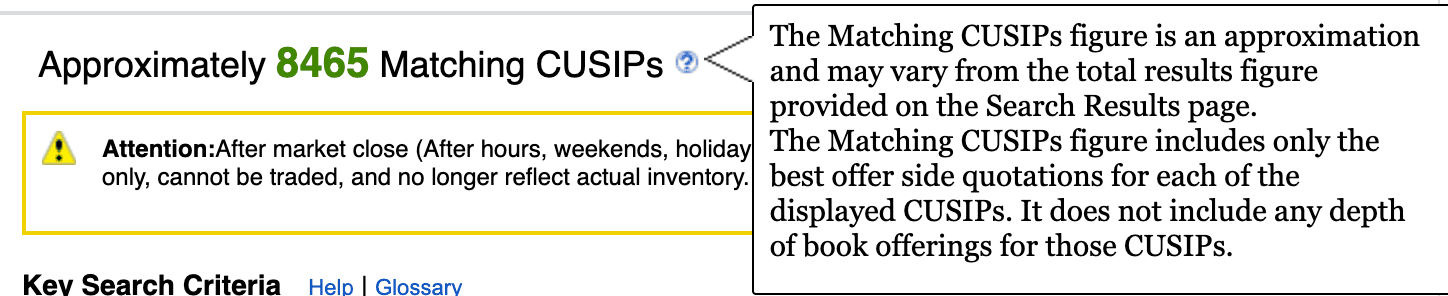

There are a few in-line help buttons that follow this hall of mirrors approach. Clicking on a question mark next to “CUSIPs” on the Fidelity site, for example, generated a wonky explanation to a question I didn’t have while raising altogether new questions about “offer side quotations” and “depth of book offerings”.

Image 1: Fidelity In-Line Help for “CUSIPs”

Most bafflingly, it proved impossible on any broker site to locate bonds by the name of the issuer. Fruitless hunts through search boxes and bond filters followed by more definitive chats with customer service confirmed that the brokers weren’t able to produce a list of bonds issued by Amazon, Proctor & Gamble, or any specific company.

Let's put this failure in some perspective. In 2023, astonishing feats of detection continue to be realized in a wide span of fields outside personal finance. Deep learning identifies genetic diseases based on facial images. Stars in photo backgrounds are used to geolocate military installations. And spectroscopy reveals early signs of stress in concrete structures as well as the presence of herring worms in Norwegian whitefish fillets. The hope therefore didn’t seem extravagant for one of the major brokers that service retail clients in the United States to be able to detect and extract the names of corporate bond issuers from the first couple of words in a bond description. It is even stranger considering that I could filter bonds using more than 20 other data points (e.g., payment frequency; call protection; ratings grade). Otherwise comprehensive systems of classification excluded the one item in which I was most interested.

As I sat there flummoxed by my inability to buy a product that the brokers presumably want to sell, it dawned on me that more sophisticated tools must be available to another class of buyer. The $127 trillion global fixed income market surely couldn’t be supported by systems as clunky as the ones available to me. Indeed, a little web research quickly revealed a host of innovations underway for institutional bond traders. Multiple teamsare working on AI-powered bond trading platforms for professionals. Meanwhile, I was stuck with hurdles that MS-DOS era systems would find trivial to solve. Despite sedulous effort over an extended lunch break, in a country that congratulates itself on the depth and sophistication of its financial markets, I could not arm-twist any retail broker into showing me bonds for sale issued by two of the top fifteen companies in the S&P 500.

Retail investors like myself can indeed purchase ETFs that provide ready access to the broad bond market. However, TreasuryDirect demonstrates that the general public is not averse to purchasing individual bonds when given an intelligible platform and attractive rates. TreasuryDirect, through plainspoken language and easy-to-access explanations, serves as an exemplar of technical elucidation for a general audience. Bonds, and the credit markets at large, don’t need to be complicated.

While equities have undergone a continual evolution on a path towards lower fees and transparency since the 1980s, despite some recent improvements, credit is marked by a generalized darkness. Well-intentioned efforts towards modernization, such as the SEC’s Fixed Income Market Structure Advisory Committee (FIMSAC), seem to have atrophied since the onset of COVID.

From the gracelessness that characterizes corporate bonds, cui bono then? Not the retail brokers, who would presumably benefit from increased trading and the commissions it generates.

Part of the resistance to reform surely resides with the broker-dealers, upstream from my retail brokers, that profit off the spread that separates buyers and sellers. Like pupils, these spreads expand in darkness.

Meanwhile, if benefits are concentrated, damages are well-distributed. Few voters likely write in to their elected representatives to complain about the clunkiness of the credit markets. The lack of retail involvement in turn prevents the development of a wider constituency for change. In this sense, clunkiness is a feature, not a bug.

Private sector firms frequently oppose oversight from government bodies. However, a failure to enact more thoroughgoing reform could eventually summon a regulatory bogeyman they would subsequently bemoan. The same firms might also find the example of TreasuryDirect invidious, a government-run platform that belies the case that enhanced transparency would be either undesirable or unattainable.